“Are YOU going to monetarily compensate me for damages/decreased value to my property when it gets broken into or I get mugged walking through the Park?” —M Smith

At the end of a quiet street in Seattle’s Magnolia neighborhood, behind a wrought iron fence and piles of dead leaves, sits 34 acres of land. The acres are unused and dead silent. A gray, old building once hosted Army classes and assemblies. Today the structure is boarded up and posted with “No Trespassing” signs.

The brick building next door with soundproof music rooms inside? That’s boarded up too. So is the small garage once dedicated to military vehicle maintenance. Moss grows on the sidewalks and parking lots. Other than a few people walking their dogs in the freezing December air, the whole place is empty. Seattle boasts more cranes than any other American city, but not a damn thing is happening here.

To most, these unused buildings at a closed army post called Fort Lawton look unremarkable. But look again through the lens of Seattle’s homelessness crisis and they represent a sort of civic Rorschach test. Because this property once belonged to the military, federal law says the City of Seattle could get a large swath for free if it agrees to use it for homeless housing. Housing advocates and city officials look at Fort Lawton and see a rare opportunity. Some residents in the neighborhood look at the same picture and see a threat.

As Seattle politicians panic about a housing shortage and homelessness crisis, basically everyone involved agrees we need more housing and we need it now. They agree housing must include not just market-rate apartments, but subsidized housing, too. And they agree the subsidized housing should serve both low-income people who might otherwise become homeless and people sleeping on the streets right now. Politicians campaign on finding new money for affordable housing and on building that housing on surplus city land. In lieu of more radical proposals—upzoning single family neighborhoods, raising taxes on corporations—it shouldn’t be that hard to build one affordable housing project on an unused piece of land.

Yet city officials are now a decade into a fruitless effort to build affordable housing at this space abutting Discovery Park. One of the most reliable forces against development, neighborhood backlash, successfully killed the last effort to develop Fort Lawton. Now, the city is making a second attempt with a proposal that includes apartments for formerly homeless seniors. On Wednesday night, the Seattle Office of Housing released a new draft environmental impact statement about the project. Another round of pushback is sure to follow.

“No housing, especially for homeless!?! Don't wreck the best open space in the city with a misdirected faux PC attempt.” — Jerry Bridges

If you feel like you’ve heard this story before, you probably have. Back in 2008, Seattle proposed a mixed-income development plan for Fort Lawton, part homeless housing, part market-rate. Opponents sued. Over two years of legal back and forth, a neighborhood group demanded more environmental review of the proposal. Eventually, the Court of Appeals agreed that under state environmental rules known as SEPA, the city needed to do more environmental review.

SEPA appeals and lawsuits are a common tactic for people trying to stop or delay construction. The Sightline Institute, an environmental think tank that advocates for market-rate housing, calls SEPA a “recipe for both obstructionism and bad urban housing policy.” By the time the Fort Lawton case was over in 2010, Seattle was still reeling from the 2008 financial collapse. The city put the project on hold.

“We’re kind of in a waiting game and we have been for 10 years,” says Chris Jowell, director of agency operations at Catholic Housing Services. His agency hopes to build apartments for homeless seniors on the site.

Last decade, a neighborhood activist named Elizabeth Campbell led the lawsuit against the city. Once a long-shot mayoral candidate, Campbell has called for “limits on growth” and fought the downtown tunnel. When former Mayor Ed Murray pitched a property tax levy for homelessness this year, Campbell registered an opposition campaign. (Murray later withdrew the levy.) Campbell’s email address includes the pseudonym “neighborhoodwarrior.” In an interview with the MagnoliaVoice.com about Fort Lawton in June, she said, “You need a lawyer and a litigation plan. You need to go guerrilla. To me it’s like a war.”

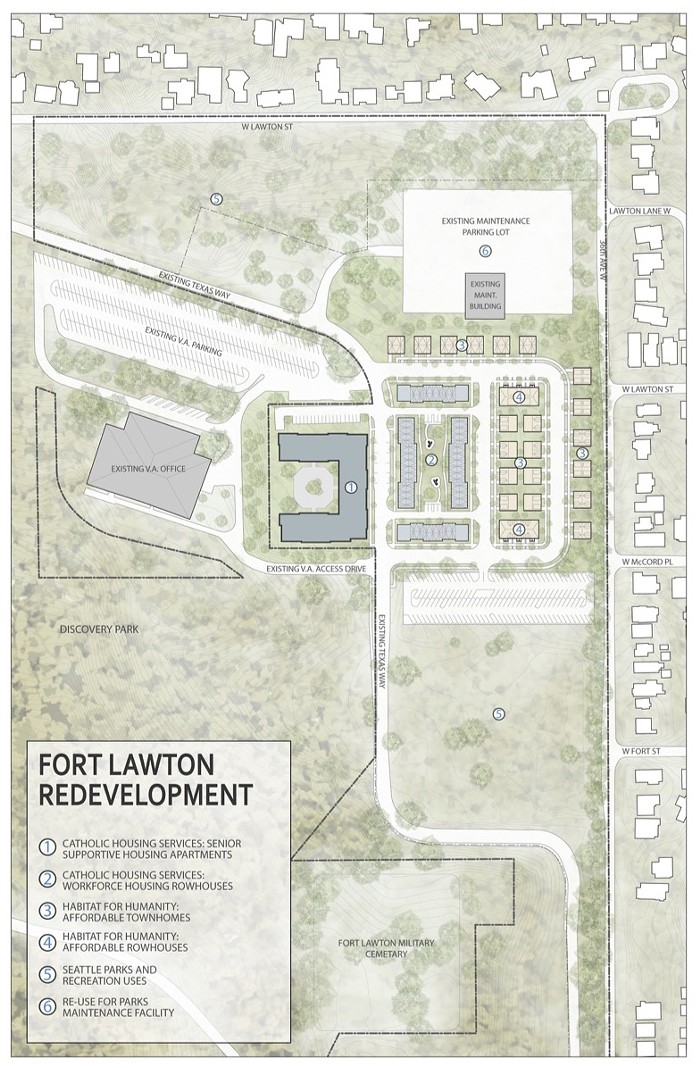

Now, the city is back with a new housing plan for the site and Campbell is back too. The Seattle Office of Housing proposes 238 apartments, row houses, and townhouses here as well as a park surrounding the housing. Campbell and a new group called the Discovery Park Community Alliance want to reserve the site for a children’s camp instead. In a letter to the city, Campbell’s alliance argues the city should restart its planning process.

Reached by phone, Campbell bristles when asked why she opposes housing at Fort Lawton. “I don’t consider it opposition to the housing because that’s a storyline that the housing people like to run, that the homeless people might like to run, that the city might like to run,” she says. Asked about the homelessness crisis and lack of affordable housing, Campbell cuts the question short. “I’m not going to go into the homelessness thing,” she says. “The homelessness people can go into their own spiel. It’s the park that I’m working on.”

“Anywhere other than near our Discovery Park.” —Dieter Plapp

Campbell may not want to talk about “the homelessness thing,” but plenty of other people do. When Seattle revealed this summer it would again consider putting housing at Fort Lawton, more than 700 public comments poured in at meetings and by email, including those featured in italics in this story. Some people prefer a school at the site. Others want a dog park or an extension of nearby Discovery Park. The feedback wasn’t all anti-housing. About 275 opposed housing on the site, almost 200 supported it, and the rest didn’t clearly take a side.

“The need for affordable housing is a life and death matter,” wrote Sylvia DeForest. “We already have Discovery Park with its unparalleled views, forests, beaches and meadows.”

“I hope that the NIMBY-ism of some of my neighbors does not block this proposal,” wrote Sarah Morgan.

But a familiar thread runs through the opposition: Fears about crime, property values, and protecting the park.

Magnolia is one of Seattle’s wealthiest neighborhoods with median household incomes exceeding $150,000 in some areas. (It’s worth noting there is a gap in the neighborhood. Areas farther from the park have a median of about $67,000 and the area near Fort Lawton $90,000, according to census data that includes a 10 percent margin of error.)

In comments to the city, neighbors worry in one breath about increased traffic from hundreds of new residents and in the next about the lack of bus service for the new residents. They say the closest grocery store—the upscale Metropolitan Market—is too expensive for low-income people.

Go door to door and the concerns are the same, if more restrained than the written comments.

“No matter what I say, it’s never going to sound good,” says resident Erica Jamir. Jamir says she’s worried about traffic, overcrowding, and how the city will determine who can live in the affordable housing. She questions the city’s policies on encampments and the millions spent on homelessness, but says she’s not anti-homeless.

“I’ve worked really hard to make a community,” Jamir says about her friendships with her neighbors. “And I want to maintain that. And it’s not a money thing. It’s not. It’s a community thing.”

Down the street, Bob Eramia answers my questions as he sets up a solarscope in his yard. He compares the proposal for around 200 units at Fort Lawton to Cabrini Green, a notorious public housing project in Chicago that once housed 15,000 people. Over objections from residents, some whose families had lived there for generations, Cabrini Green was eventually torn down.

“It’s going to be a disaster,” he says. Inside the house, Eramia’s wife Sue says the housing plan should be smaller. “That’s going to overwhelm us,” Sue says.

“I’m a liberal, but they call us names,” she says. “They’ve been calling us NIMBY...saying we’re against the homeless and that’s not true.”

Yiming Sun, who’s lived in the neighborhood four years, draws a comparison to Pioneer Square. “We definitely don’t want our neighborhood becoming one of those.”

Some who oppose housing here don’t actually know the specifics of the city’s plan, including the types of housing that would be built. Some are worried about Discovery Park, even though this project would not touch the 534-acre park. One is worried about the wildlife in the area. Two residents imply that, as a millennial, I have too much faith in the city or the nonprofits that plan to build the affordable housing.

A woman watering the plants on her front porch won’t give me her name but says she simply doesn’t trust the city to follow through on its plans. Yes, she’s seen subsidized housing in other neighborhoods that “looks nice”, but she doesn’t think Magnolia “can bear a lot more housing.”

“I don’t think people are xenophobes,” she says. “They want it to be done thoughtfully.”

“Locate a homeless community inside Magnolia and watch the destruction of a beautiful neighborhood. We will be moving out and taking our tax dollars away from you. Watch out for the wealthy, because that's what you have underestimated, our power.” —Marilene Bysshe

It’s no secret that the region has a homelessness emergency.

At last count, 11,643 people across King County were experiencing homelessness, 8,522 of them in Seattle. Countywide, a little more than half of people experiencing homelessness live in shelters. The rest live on the streets or in vehicles, abandoned buildings, or tents. In a city survey of people experiencing homelessness, 93 percent said they would move inside if housing was available.

Of King County’s homeless population, 6 percent are American Indian or Alaska Native, while those groups make up just 1 percent of the county’s general population. “This is unacceptable in place that is named after an iconic indigenous leader, Sealth,” local tribal leaders from the Coalition to End Urban Native Homelessness wrote in a letter to the city. They are calling for “Native-provided housing and culturally appropriate support services” at Fort Lawton.

When it comes to housing for people experiencing homelessness, the line to get inside is long. While 2,370 adults received affordable housing or rent assistance in the first six months of the year, just 77 single adults in King County were referred to the type of supportive housing that would be provided at Fort Lawton for homeless seniors. Supportive housing includes services on site.

In a city drawing a thousand new people a week, market-rate options are bleak, too. Median rent for a one-bedroom in Seattle is now between $1,300 and $1,900. And while median rent in Washington has increased 17 percent since 2006, median income has increased just 7 percent, according to data compiled by the state Department of Commerce.

To address its housing needs between now and 2030, Seattle will need about 27,500 more homes for people making the lowest incomes, according to the Housing Development Consortium. For people with higher incomes but who are still making less than area median income, the city will need another 20,000 units.

Whether those numbers can sway neighbors is another question. Compared with the first effort to develop Fort Lawton, there is now more “urgency around homelessness,” says Jowell, from Catholic Housing Services. “It doesn’t necessarily change people’s feelings about things happening in their neighborhoods, but the emphasis on homelessness is much greater.”

Carol Burton, a trustee of the Magnolia Community Council, says her group is divided and hasn’t yet taken an official position on the housing proposal. She’s already made up her mind. A no-nonsense former biologist with a British accent, Burton says she supports affordable housing on the site. “People have to live somewhere,” she says, “and they’re people.” The Fort Lawton site, Burton says with a sigh, as if she’s in yet another debate with her neighbors, is “almost all paved. It’s not like you’re saving the environment or anything.”

Burton moved to Magnolia nearly 20 years ago and remembers something a neighbor told her then: “The thing you have to remember is in Magnolia, they say, ‘I don’t know what it is, but I don’t like it.”

“Enough is Enough! Drive through this city and it is depressing. The once beautiful, ‘Emerald City’ is turning into a wasteland of tents and trash everywhere. We cannot this family neighborhood into another homeless destination”. —Jenny Taylor

Magnolia—a neighborhood named by a lieutenant who wrongly identified the area’s Madrona trees—is no stranger to slow progress and class conflict. For decades, Fort Lawton took up much of the neighborhood. Soldiers used the site during World War II as a camp for prisoners of war. Over the years, the post has been transformed piece by piece. In the 60s, the Army transferred most of the area to the city for a park. In March of 1970, a group of Native American leaders and supporters occupied Fort Lawton to draw attention to the needs of urban Indians and to retake the land. The Daybreak Star Cultural Center formed out of that action. Part of the area is a cemetery. Another part includes restored historic houses now worth about $2 million each. The post finally fully closed in 2012. The empty buildings and parking lots are the final piece to go.

This week, the city will start the next round of its battle with the neighborhood. A draft environmental impact statement (EIS) released Wednesday considers several alternatives but shows the city’s preference for affordable housing on the site. Of the total 34 acres, most of that would be open space, owned either by the city or the school district. Seven acres would be housing, less than half of the 19-acre development proposed in 2008. That change was partially a response to neighborhood complaints about the scale of new development, according to the Office of Housing.

The city’s preferred affordable housing plan would include 75 to 100 affordable row houses for rent, 85 apartments for homeless seniors, and 52 row houses and townhomes for purchase built by Habitat for Humanity. The affordable rentals would be designated for people making up to 60 percent of area median income or $57,600 for a family of four. The housing for purchase would be for people making up to 80 percent area median income or $72,000 for a family of four. In total, the project would house about 596 people and include 266 parking spaces, according to the EIS. Federal law allows the military to give the city free land for parks and homeless housing. The city would purchase the segment used for affordable rental housing.

The homeless housing, built by Catholic Housing Services, would have services on site, including 24-hour access to counselors, case management, help with Medicaid or Medicare, and transportation to healthcare.

City officials will now take another round of public comment before finalizing their report. Then, they could face another possible appeal.

Asked recently whether she plans to appeal or sue again this time around, Campbell, who led the 2008 effort, told The Stranger, “Well, of course.”

This article has been updated to clarify the number of adults referred to housing.